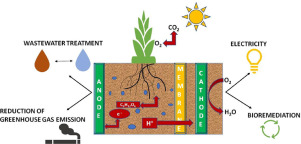

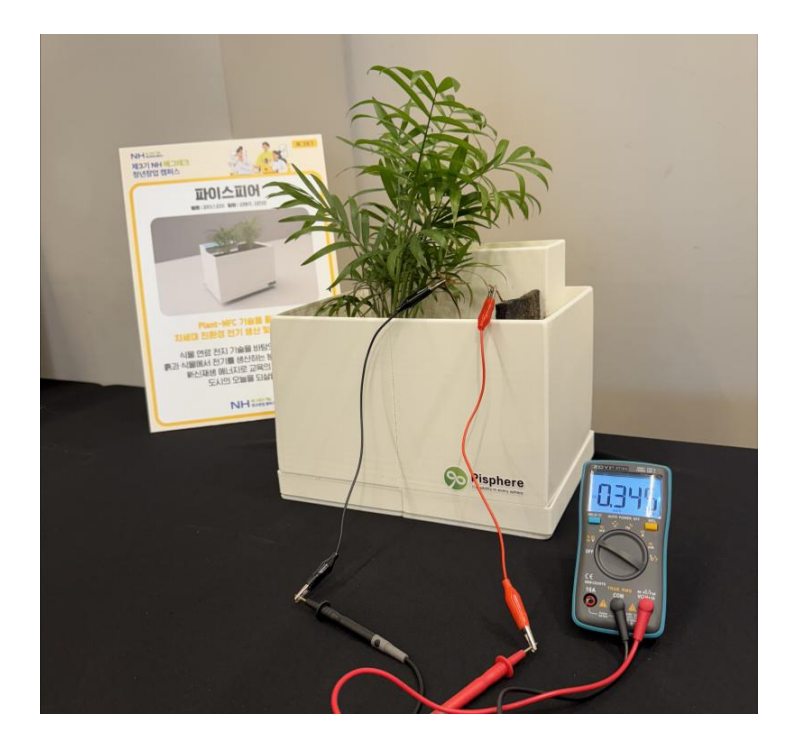

The global transition toward sustainable energy sources is a multifaceted challenge, demanding innovation that moves beyond conventional solar, wind, and hydro power. While these technologies are crucial, they often suffer from intermittency, high material costs, and significant land footprint. A compelling alternative lies in harnessing the inherent power generation capabilities of biological systems—specifically, the symbiotic relationship between plants and electrogenic microorganisms. This is the domain of the Plant-Microbial Fuel Cell (P-MFC), a technology that Pisphere has refined from a laboratory curiosity into a commercially viable, decentralized power solution.

This article serves as a deep technical exploration into the electro-microbiological principles that underpin Pisphere’s innovation. We move beyond the simple concept of “plants making electricity” to dissect the complex biochemical pathways, microbial mechanisms, and engineered architecture that allow for continuous, low-power energy generation. The Pisphere system is not merely a battery; it is a living, self-sustaining bio-hybrid generator, representing a paradigm shift in how we conceive of renewable energy.

Section 1: The Photosynthetic Engine and Rhizodeposition

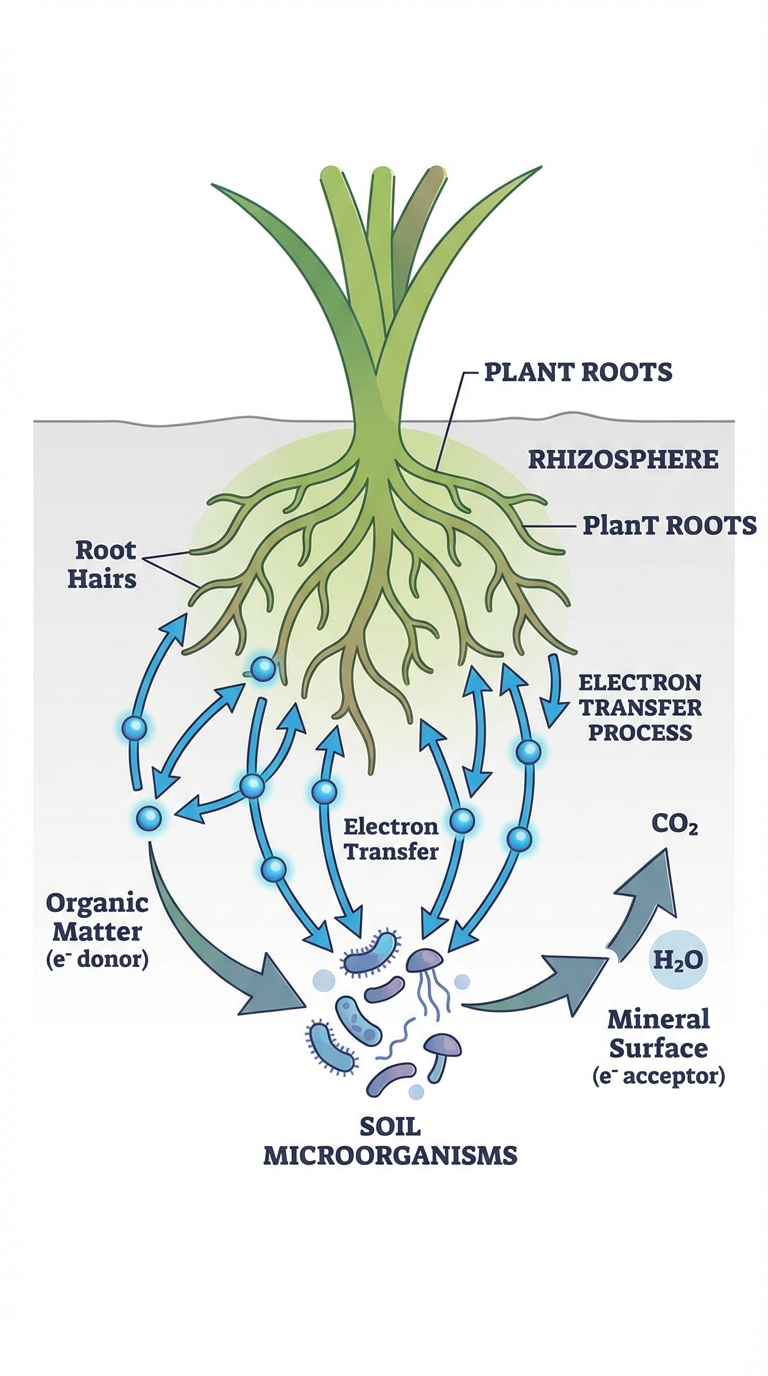

The foundation of the P-MFC system is the plant itself, acting as a continuous solar energy converter. Through photosynthesis, plants capture atmospheric carbon dioxide and convert it into complex organic compounds, primarily sugars (glucose), which serve as the ultimate fuel source for the entire system.

The critical step for energy harvesting, however, occurs not in the leaves, but in the soil surrounding the roots—the rhizosphere. Plants are highly efficient at translocating photosynthetic products from the leaves (source) to the roots (sink). A significant portion of these products, estimated to be between 10% and 40% of the total fixed carbon, is actively secreted by the roots into the rhizosphere in a process known as rhizodeposition.

The Chemical Fuel Mix

Rhizodeposits are a complex cocktail of organic molecules, including:

- Low-molecular-weight compounds: Sugars (glucose, fructose), organic acids (acetate, succinate, lactate), and amino acids. These are highly bioavailable and serve as the primary electron donors for the electrogenic bacteria.

- High-molecular-weight compounds: Polysaccharides and proteins, which require initial breakdown by non-electrogenic microbes before they can be utilized.

- Mucilage and cell lysates: Structural components that contribute to the overall organic load.

The continuous secretion of these compounds ensures a steady, renewable supply of substrate for the microbial community. Crucially, this process does not require the plant to be harvested or damaged; the energy is derived from the natural, continuous cycle of root exudation. This is the key distinction between P-MFC and traditional biomass-based energy systems, which rely on destructive harvesting.

Maintaining the Anoxic Environment

For the Microbial Fuel Cell to function, the anode chamber must maintain an anaerobic (oxygen-free) or at least anoxic (low-oxygen) environment. In the natural rhizosphere, the high metabolic activity of soil microorganisms rapidly consumes available oxygen, creating localized anoxic zones, particularly deeper in the soil profile. Pisphere’s design leverages this natural phenomenon.

The submerged or embedded nature of the P-MFC anode creates a controlled environment where the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) is thermodynamically unfavorable at the anode surface. This forces the electrogenic bacteria to utilize the solid-state anode as their terminal electron acceptor, a process that is the very definition of microbial electrogenesis. The plant’s root system, by consuming oxygen and promoting microbial activity, actively contributes to maintaining the necessary electrochemical gradient.

Section 2: Microbial Electrogenesis and Extracellular Electron Transfer

The true power of the Pisphere system lies in the specialized bacteria that colonize the anode surface, forming a dense, electrically active biofilm. These are the exoelectrogens, or electrochemically active bacteria (EAB), capable of transferring electrons generated during their metabolic processes directly onto an external electrode.

Pisphere utilizes Shewanella oneidensis MR-1, a model organism in bio-electrochemical systems, known for its exceptional versatility and efficiency in Extracellular Electron Transfer (EET).

The Metabolic Pathway

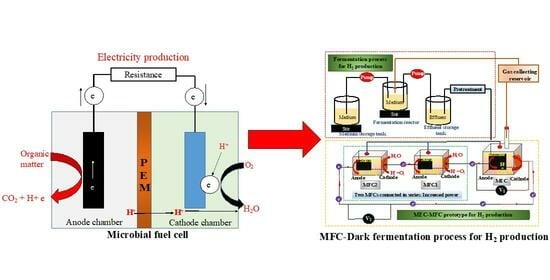

The process begins with the bacteria metabolizing the organic substrates (e.g., acetate, lactate) from the root exudates. This metabolism, primarily through the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, generates electrons and protons. In a typical aerobic environment, these electrons would be passed down an electron transport chain to reduce oxygen (O₂). In the anaerobic environment of the P-MFC anode, however, the bacteria must find an alternative electron sink.

This is where the anode comes in. The electrogenic bacteria have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to “breathe” solid-state materials, effectively using the anode as their final electron acceptor. The half-reaction at the anode can be simplified as:

$$ \text{Organic Substrate} \rightarrow \text{CO}_2 + \text{Protons} (\text{H}^+) + \text{Electrons} (e^-) $$

Mechanisms of Extracellular Electron Transfer (EET)

S. oneidensis MR-1 is particularly effective because it employs multiple, redundant pathways for EET, maximizing current generation:

-

Direct Electron Transfer (DET): The bacteria physically attach to the anode surface. Electrons are shuttled across the outer membrane via specialized proteins, primarily c-type cytochromes (e.g., MtrC and OmcA). These cytochromes act as terminal oxidases, transferring electrons directly to the conductive material of the anode. This mechanism requires close proximity and a robust biofilm.

-

Mediated Electron Transfer (MET): The bacteria secrete soluble redox-active molecules, known as electron shuttles (e.g., flavins). These shuttles are reduced by the bacteria, diffuse away from the cell, transfer the electron to the anode surface, and then return to the cell to be reduced again. This allows bacteria not directly attached to the anode to contribute to the current. S. oneidensis MR-1 is a prolific producer of flavins, making this a highly efficient pathway in the Pisphere system.

-

Conductive Pili (Nanowires): While less dominant in Shewanella compared to Geobacter, the concept of electrically conductive appendages (nanowires) provides a pathway for long-range electron transfer within the biofilm matrix. This mechanism allows for the creation of thick, multi-layered biofilms where only the outer layer is in direct contact with the electrode.

The Pisphere system is optimized for the growth and activity of S. oneidensis MR-1 through careful selection of the anode material and the surrounding electrolyte, ensuring a high rate of electron transfer and thus, maximum power output.

Section 3: The P-MFC Architecture and Electrochemical Dynamics

The Pisphere device is an elegantly engineered bio-electrochemical reactor designed for maximum efficiency and long-term stability in a real-world environment. It adheres to the fundamental architecture of a fuel cell, comprising an anode, a cathode, and a separator, but with the unique integration of a living plant system.

Anode and Cathode Design

-

Anode (The Electron Collector): The anode is the heart of the power generation. It is typically made of a highly conductive, biocompatible, and porous material, such as carbon felt or graphite granules. The porosity maximizes the surface area for microbial colonization, which is directly proportional to the power output. The anode is buried in the root zone, ensuring constant access to the organic exudates and the anaerobic conditions.

-

Cathode (The Electron Acceptor): The cathode is typically placed near the soil surface or in a separate chamber exposed to air. Its function is to complete the circuit by accepting the electrons that travel through the external load. The reaction at the cathode is the Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR):

$$ \text{O}_2 + 4\text{H}^+ + 4e^- \rightarrow 2\text{H}_2\text{O} $$

The efficiency of the cathode is often the limiting factor in MFC performance. Pisphere’s design focuses on maximizing the air-cathode interface and utilizing catalysts (often carbon-based) to lower the activation energy of the ORR.

The Role of the Separator

In many MFC designs, a Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) is used to separate the anode and cathode chambers. The PEM allows protons (H⁺) generated at the anode to migrate to the cathode, maintaining charge neutrality in both chambers and completing the internal circuit. While a traditional PEM offers high performance, it can be costly and prone to fouling.

In simplified, low-power P-MFC systems like those optimized for Pisphere’s applications (e.g., smart sensors), the soil itself can act as the separator, allowing proton migration through the electrolyte (soil water). This separator-less design significantly reduces manufacturing complexity and cost, making the technology highly scalable and cost-effective for distributed, low-power applications.

Performance and Energy Density

Pisphere’s P-MFC technology is characterized by its remarkable stability and energy density relative to its footprint. The system is designed for 24/7 continuous operation, a significant advantage over solar power, which is inherently intermittent.

The reported production capacity of 250-280 kWh per 10m² annually is not intended to power a household, but rather to provide reliable, off-grid power for low-consumption devices. This output is perfectly suited for:

- IoT Sensors: Powering smart agriculture monitoring systems, soil moisture sensors, and environmental data loggers.

- Educational Kits: Providing a tangible, hands-on demonstration of bio-electricity.

- Public Infrastructure: Powering low-energy LED lighting, small displays, or remote monitoring stations.

The low maintenance cost of $10-15 USD per year is a direct result of the system’s biological nature. Unlike solar panels, which require cleaning and eventual replacement, or wind turbines, which have moving parts, the P-MFC is self-sustaining, requiring only the continued health of the plant and occasional electrolyte management.

| Feature | Plant-MFC (Pisphere) | Solar PV (Small Scale) | Wind Turbine (Micro) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Source | Plant Exudates (Continuous) | Sunlight (Intermittent) | Wind (Intermittent) |

| Operation | 24/7, Day & Night | Day only | Wind-dependent |

| Maintenance Cost (Annual) | $10 – $15 USD | $20 – $30 USD | $40 – $60 USD |

| Carbon Footprint | Carbon Neutral/Negative | Low (High initial embodied) | Low (High initial embodied) |

| Scalability | Modular, Embedded | Modular, Surface Area Dependent | Height Dependent |

| Primary Output | Low-Voltage DC | Low-Voltage DC | AC (Requires Inverter) |

Section 4: The Bio-Hybrid Advantage: Carbon Neutrality and Zero Waste

The scientific elegance of the Pisphere system extends beyond mere power generation; it embodies a truly circular, zero-waste, and carbon-neutral technology. This bio-hybrid approach offers environmental benefits that are unattainable by purely abiotic energy sources.

Carbon Sequestration and Neutrality

The P-MFC system is inherently carbon-neutral, and potentially carbon-negative, due to the central role of the plant. The plant’s primary function is to draw CO₂ from the atmosphere and fix it into biomass. While some of this carbon is released as CO₂ during microbial respiration at the anode, the net effect is a closed-loop system where the fuel source is continuously regenerated from atmospheric carbon.

Furthermore, the embedded nature of the technology means that the system is integrated into the soil ecosystem, promoting healthy soil structure and microbial diversity. The system does not produce toxic byproducts, nor does it require the mining or processing of rare earth minerals, which are common in other renewable technologies. The only “waste” product is water, produced at the cathode, and the spent microbial biomass, which naturally integrates back into the soil.

The Role of Bio-Augmentation

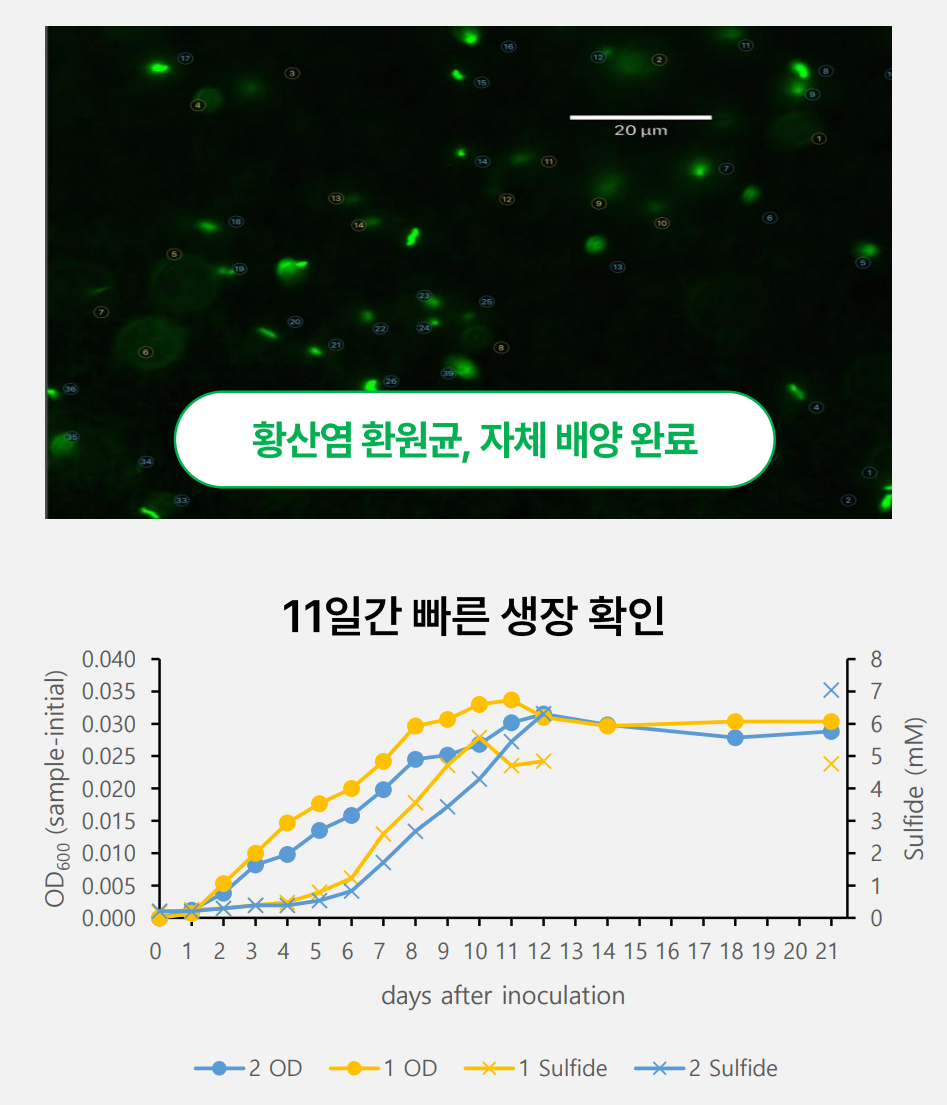

Pisphere’s use of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 is a form of bio-augmentation, a strategic intervention to enhance the natural electrogenic capacity of the soil. While native soil microbes can generate current, the introduction of a highly efficient exoelectrogen like S. oneidensis MR-1 significantly boosts the current density and overall power output.

This requires careful management of the microbial community. The system must be designed to favor the growth and colonization of the augmented species while maintaining a stable, non-competitive environment. Factors such as pH, temperature, and the concentration of electron donors (rhizodeposits) are precisely controlled by the system’s design and the plant’s natural processes. The stability of the S. oneidensis MR-1 biofilm is key to the long-term, low-maintenance operation promised by Pisphere.

Section 5: Future Trajectories and Scaling the Bio-Power Frontier

The current state of P-MFC technology, as demonstrated by Pisphere, is focused on low-power, distributed applications. However, the scientific principles suggest a clear trajectory toward higher power density and broader application.

Increasing Power Density

The primary scientific challenge in P-MFC is increasing the power density (W/m²). Research is focused on several key areas:

- Anode Material Science: Developing novel, highly conductive, and porous materials with tailored surface chemistries to promote stronger and more active biofilm adhesion. Graphene-based composites and modified carbon fabrics are promising candidates.

- Cathode Optimization: Improving the kinetics of the Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR) at the cathode. This involves exploring non-platinum group metal (non-PGM) catalysts and optimizing the cathode structure for better air diffusion and water management.

- Plant Selection and Engineering: Identifying or genetically engineering plant species that exhibit higher rates of rhizodeposition and are more tolerant of the anoxic conditions required for the anode.

Integration into Smart Infrastructure

The true potential of Pisphere lies in its seamless integration into the built and natural environment. The technology is inherently space-efficient and embedded, meaning it can be deployed in urban green spaces, vertical gardens, and agricultural fields without requiring dedicated land or visual intrusion.

Consider the application in IoT Agriculture and Smart Cities. A network of Pisphere units, embedded beneath public planters or agricultural rows, could autonomously power a mesh network of environmental sensors. This creates a self-sustaining, energy-independent monitoring system that provides real-time data on soil health, microclimate, and crop status, all while sequestering carbon and maintaining green infrastructure.

The scientific journey from the discovery of electrogenic bacteria to the commercial deployment of Pisphere is a testament to the power of bio-hybrid engineering. By meticulously optimizing the photosynthetic engine, the microbial electrogenesis, and the fuel cell architecture, Pisphere has unlocked a new frontier in renewable energy—one that is literally rooted in the earth and powered by life itself. The deep science behind Plant-MFC is not just about generating a few watts; it is about establishing a new, symbiotic relationship between technology and nature, paving the way for a truly sustainable energy future.